image from The Harvard Med School Center for Hereditary Deafness

| MadSci Network: General Biology |

Em-

That's a really great question! It does seem weird that people who can't seem to hear anything can speak.

I'll try to answer your question the best I can. I will undoubtedly leave out some bit of information or detail, but I've tried to give you links to find more information in case you're curious.

The first consideration is: When did they become deaf? If they became deaf after they had learned to speak, they should be able to faithfully repeat what they've learned. The quality of their pronunciation may drift a bit - I'll discuss that below.

But what about if they've been deaf from birth? The story

gets a little more clear when we ask the

question: what is deafness? Well, we both know it means that a person

can't hear. But there are different reasons

why that could be. To understand, let's look at the structure of the

ear:

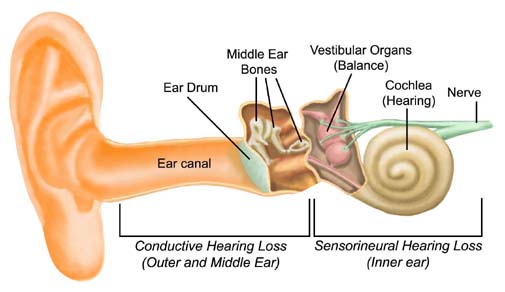

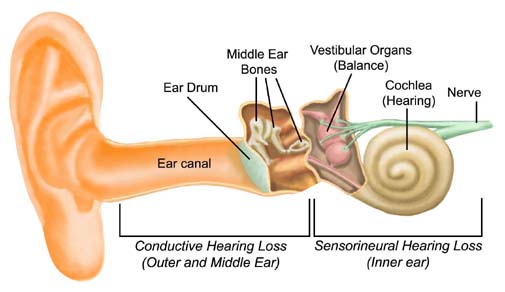

The major parts of the ear are the pinna, or ear lobes, the eardrum, middle ear bones, cochlea, and the auditory nerve, as diagrammed above. And the diagram makes references to two types of hearing loss: "Conductive Hearing Loss" (CHL) and "Sensorineural Hearing Loss." (SHL) These two, major classes of deafness are very different in cause and thus can different effects on the way the person can deal with sound. I'll describe them in a minute.

The outer and middle ear transduce vibrations in the air

into movement of fluid in the cochlea. The

ear drum vibrates when sound hits it, and this causes the bones to

vibrate, too. The stirrup bone is connected to a

little flap on the cochlea, called a 'window' (sort of like another

eardrum, but on the cochlea). A simplified

description of the cochlea is that it's a fluid filled tube. When the bone

presses against the cochlear window, it

increases the pressure of fluid inside, and specially designed receptors

can sense this pressure. A more detailed

description of what happens can be found here.

These specialized receptors in the cochlea transform the

pressure signal into a neural signal, and

the nerve carries this transformed signal to the brain, where it can be

interpreted. These are the real 'sound

translators.'

So if we think of 'what makes a person deaf?' Two major

ways arise: the structures which transform

the air vibration into fluid vibration could be damaged [CHL] ; or the

structures which transduce a pressure signal

into a neural signal (or carry that signal to the brain) could be damaged

[SHL]. If a person has CHL, the sound

translator (cochlear/nerve) still works, so there is a greater chance they

can hear. They might be

able hear themselves speak (because in talking, we vibrate our own bones a

bit), but not outside sounds. Some

hearing aids work by vibrating the skull a bit near the ear bones, and

that provides enough vibration for the

cochlea to work. In more extreme cases, special devices can be implanted

into the cochlea. These Cochlear

Implants have been quite successful. They basically work by bypassing

the outer and middle ear bones, and

stimulate the cochlea directly.

If a person has SHL, the situation is much more dire. We

don't know enough about how the nervous

impulses are sent, organized, and understood by the brain to really

control this. With our current technology, we

can't do much for these patients.

An analogy could be this: If your light turns off, it

could be because the lamp itself is broken

(CHL) or that the bulb is out (SHL). The lamp merely provides a round

socket to hold the light bulb and connects it

to the power source; you could probably plug a wire into the socket and

make a little socket out of metal to get the

bulb to work (but DO NOT try this!!!). But the bulb is what's designed to

turn an electrical current into light. We

could plug every lamp into every socket in the world, but if there are no

bulbs, we have no light... In the same

way, if we have no cochlear or nerve, we can't get the neural signal to

the brain. Unfortunately, replacing cochleas

isn't as easy changing light bulbs.

SO, back to your original question: A person who is born

with CHL may learn to speak using devices

which bypass some of the auditory structures or hijack the cochlea. The

speech may not be perfect, but it should be

good enough to communicate. But a person with SHL is highly unlikely to

be

able to make proper sounds for speech (at least in this day and age). (or

if they became deaf after learning to

speak, their speech may become more distorted, as they don't know to

correct any mispronunciations)

I hope this sheds some light on how people hear, and how a

person who is deaf may be able to make

sound!

Here are some the sites I used for this info:

http://deafness.about.com/

http://hearing.harvard.edu/ind ex.html

http://www.med.harvard.edu/publications/On_The_Brain/Volume3 /Number4/Cochlear.html

http://thalamus.wustl. edu/course/audvest.html

-Alex Goddard

cgoddard@fas.harvard.edu

Try the links in the MadSci Library for more information on General Biology.